When I was in my mid-20s, I saw it everywhere—on billboards, magazines, newspapers, etc.

It was Apple’s campaign that featured pictures of historical figures known for their innovativeness, along with the text, “Think Different.”

As I entered this summer vacation following our tremendous Gather for Good: The Future is Here, with Sam Altman, Zoë Hitzig, Tom Preston-Werner, and Varun Soni, on my mind was the future of education: Amidst the very real, monumental challenges, this is a thrilling time too of opportunity for humanity. The phrase, “Think Different” kept coming into my thoughts.

An increasingly risky proposition is automated thinking and passive acceptance of conventional ideas and approaches as Truth (about schools, education, and otherwise). Consider AI’s defeat of the grandmaster of the game “Go.” Developed in China in the fifth century BCE, Go is known as the most complicated board game in history. AI beat the grandmaster not because it was fed millions of game scenarios and used the best move ever made. Rather, AI made a move that no expert Go player had assumed was workable —and AI won the day.

Looking beyond our assumptions is tough. Metaphorically, it’s like asking a fish to describe water. In this moment though, we are called to look above our automatic assumptions and ask, How do we prepare our children for their futures, not our pasts? To harness this exhilarating time in history for its positive potential for our children, we need to be brave. We need to be bold.

With that, here are four worthy ways we can think differently to ideally serve children’s and adolescents’ education:

1. Move away from putting children in single-year grades based on biological age and requiring them to change teachers each year.

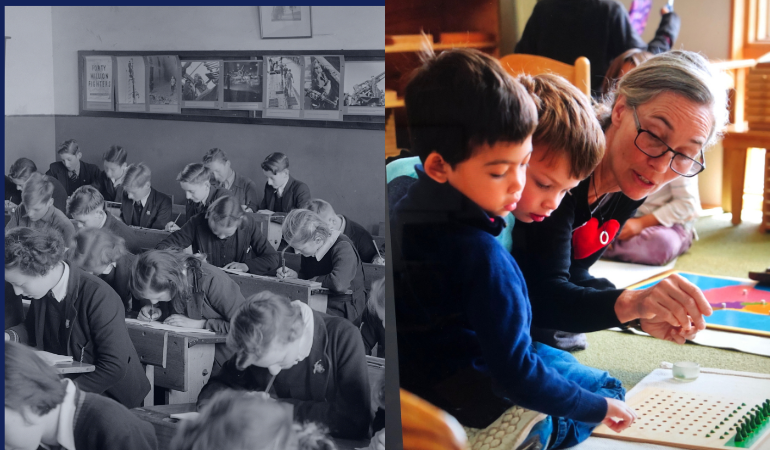

While a convenient organizing practice, there are three major losses with the current conventional assumption that schools should follow the model of single-year classrooms:

First, it pressurizes that single year for children to learn at the same pace. Some children become highly bored, confined to that single year’s curriculum that they find lacks enough challenge or variety; boredom in school deadens their once fiery intrinsic curiosity for learning; school boredom can have lifelong deleterious impacts. Conversely, other students risk being unnecessarily labeled “slow” or “remedial.”

In multi-aged environments, students can advance into curricula far beyond their single-grade levels. And, if children need more time to develop skills and understanding, the multi-aged, multi-year classroom supports this. This benefits children’s healthy maturation of their sense of self. It reduces the risk that they’ll instead develop a limiting internal narrative of “I’m not smart”—all due to the arbitrary decision to group children by single ages, as well as the assumption that children of the same biological year age should learn at the same pace.

Second, the conventional model deprives children of the benefits we adults get to enjoy in the world beyond school: working and learning from—as well as being mentored by and mentoring—peers of a variety of ages. In multi-aged, multi-year classrooms, children enjoy being mentored by older peers. Later, they enjoy the thrill of learning leadership through eventually mentoring with empathy their younger classmates; when they mentor, they discover the truism too that the best way to learn something is to teach it. Their own understanding deepens as they guide younger peers.

Third, as Adam Grant noted in his article last year, recent research shows that students enjoy better learning experiences and outcomes when they get to spend more than one year with their teachers; the depth of their teacher’s understanding of who they are as learners has a salutary effect.

2. Actively Foster Healthy Viewpoint Diversity.

It is a new world of deepfakes and nefarious bots. The validity of images we see and information we read is increasingly compromised (and then there are “AI hallucinations…”).

To effectively sift through what they see, read, and hear to identify what is valid from what is false, it is essential for our children to develop robust capacities for logical, critical thinking. From both ends of the political spectrum, though, there seems to be now an accepted assumption that if a student is at all upset by what they read and learn about, it means it must be bad and should be removed.

However, as we can each surely recall from our own lives, we actually get smarter when we encounter information or viewpoints that differ from and challenge our own: The path to growing critical thinking skills is paved by these moments that push us to wrestle with factual information and other’s viewpoints that contradict our assumptions.

The great, daunting task for educators is then to foster learning environments that are both highly open to a wide variety of perspectives and beliefs and psychologically safe enough for all students; research is conclusive that when students don’t feel safe, they don’t learn as well or as much. (Feeling psychologically unsafe can be caused by feeling one does not belong and is not wanted in an environment.)

A democracy like ours thrives when its citizens are capable of deep listening and critically considering all ideas to find the most valid conclusions and solutions—regardless of who, or which group, presents them. Schools will support our democracy’s health by building such capacities in students. This calls for dropping the assumption that in today’s fractured political climate, educators must entrench themselves in camps of specific worldviews and vociferously and blindly argue their rightness regardless of facts and other perspectives.

(To consider this topic further, I recommend the book, “The Coddling of the American Mind,” by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff.)

3. Emphasize Experiential, Hands-On Learning.

Fifty-three percent of U.S. students in grades 5 through 12 report being disengaged in school. Experiential education fosters engagement: When students deepen their more abstract academic work with direct applications of their studies, learning comes vibrantly alive and relevant; it further solidifies their understanding, too. (e.g., World language students practicing speaking in Spanish to Spanish-speaking residents of a local convalescent home; chemistry students troubleshooting the water chemistry in the school’s aquaponic system to then successfully growing produce to sell; geometry students utilizing their learning to decide on the ideal angle for the garden’s water drainage and then utilizing surveying equipment to accurately dig these, etc.)

The assumption that only disembodied, abstract work is rigorous misses the fact that hands-on learning powerfully deepens understanding by making abstract ideas concrete. Having an experience in which we apply our learning in the world makes the learning much more likely to stick. Further, we might assume a high-tech classroom is a better classroom. That was the great promise in the early-2000s when most schools rushed to get laptops and iPads into every student’s hands. We now have troves of data to show decidedly disappointing results of this promise.

Hands-on learning also supports students’ well-being: Today, more and more of our lives are mediated by digital devices, and even much of our social and work life is virtual. Just as romantic comedy movies may give us a sort of whiff of the feeling of love but are not even close to as substantive as the real thing, virtual life and virtual human relationships are not enough for any of us. (This may be connected to why half of Americans now report being lonely.) Our youth need tangible, physical life and other complex humans to encounter directly and to learn from—including learning how to relate effectively with other people.

4. Honor the Dignity and Potential of Each Child’s Individual Nature and Interests.

As Jonathan Haidt points out in his new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, the dramatic rise in youths’ levels of anxiety and depression (as further documented by rates of youth suicide, which rose 62 percent amongst US youth from 2007 to 2021) has direct links to the ubiquity of smartphones and social media in children’s hands.

As we know, endless social comparisons are systemic to our online lives, leading many to the psychological phenomenon of “compare and despair.” Schools need to serve as prophylaxis against the mental health crisis, not contributors to it.

The life-giving message schools can send to children is that they are already whole and inherently worthy. The driver of learning—in and outside of school—is the thrill of discovery of understanding and the mastering of skills.

There need not be a narrow definition of what makes one student more worthy of affirmation (or gold stars, treats, “student of the month” awards, or verbal praise) to motivate students to strive. There need not be an implicit message that a student’s purpose in life is to win praise (or “likes”) from others—peers or teachers.

If our students internalize a profound love for learning itself because learning, growing, and accomplishing goals feels amazing, this remains its own powerful motivator and reward. And, these students will flourish in the ever-changing, increasingly complex world in need of dynamic thinkers and problem solvers.

Finally, we can break our assumption that everything needs to be uniform: it sends an empowering message when we expand curriculum options so that students can also spend time diving deeply into topics and activities about which they feel individually passionate: Your nature and inner inclinations matter! You matter!

Of course, if it sounds like I am describing your child’s Montessori experience, I am. Dr. Montessori’s prescience and insights are awe-inspiring, indeed (there’s a reason I’m so passionate about my 10th year heading MMS). And, schools need not adopt and identify fully as Montessori schools to harness many of the powerful principles and practices that are so needed today.

The Power of the Possible

In 1954, England’s Roger Bannister did what the world assumed was impossible: He was the first recorded person to run a mile in under four minutes. Equally telling is that soon after he proved that it was indeed possible, many people were then able to run an under-four-minute mile. What we assume is possible (or impossible) profoundly affects what actually comes to be.

How grateful we are then for the boldness of Dr. Maria Montessori to think differently: She was told only men could be doctors, and she went on to become one of the first female physicians in Italy. Then, as an educator, she broke through an endless array of conventionally held assumptions about children and how they learn best. (In recognition of the value of her boldness in transcending those assumptions, Dr. Montessori was nominated for a Nobel Prize three different times.) In many ways and areas, the results of authentic Montessori education for children and adolescents are analogous to breaking the four-minute mile: We now know it is possible for students to love school and learning and become flourishing, independent, successful adults.

As Head of School, Sam is responsible for ensuring that Marin Montessori flourishes and that the School’s mission is brought to life each and every day.