You have two minutes.

Be honest: What is your initial reaction to seeing such a math problem? Panic? Aversion? An immediate flashback to one’s worst fears of middle school mathematics?

Or is it possible to feel curiosity and excitement?

For most of us, the answer is no. Recently, though, I saw firsthand how that answer might become a yes.

Why Many of Us Hate/Fear/Avoid Math

Math anxiety was already a hot topic 25 years ago when I was a student, and it influenced my decision to become a math teacher. I even wrote a senior thesis about it. Numerous studies have been conducted over the last sixty(!) years to identify its pervasiveness, causes, and solution strategies.

And yet, math anxiety continues to be as prevalent as ever. Approximately 93 percent of adults in the US report experiencing some level of math anxiety.

In their 2001 study, Ashcraft & Kirk defined math anxiety as “feelings of panic, tension, and helplessness aroused by doing math or even just thinking about it.” Much of this anxiety is linked to testing anxiety with an emphasis on precise, correct answers, as opposed to reasoning, processes, and understanding of applications.

The immediate result of math anxiety is loss of short-term working memory, impaired reasoning, and accuracy, feelings of fear, and even physiological effects such as clammy hands, lightheadedness, and upset stomachs.

The long-term result is an aversion to mathematics, loss of motivation, and feelings of defeatism.

Considerable efforts are being made to undo these widespread, systemic obstacles, including an emphasis on the growth mindset as it applies to mathematics education, and a greater focus on processes and communication of understanding as key learning objectives (and not strictly test scores).

Stanford professor Jo Boaler’s Youcubed workshops for math teachers have shown promising results, yet dismantling over a half-century of accepted practices of mathematics instruction cannot happen overnight.

For most students, the experience of math class, aside from better calculators and graphing software, is not all that different from their parents’ experience.

As a veteran math teacher, I feel keenly aware of the threat of math anxiety, particularly as it catches hold of adolescents in the middle school years. My goal is to impede it at every opportunity.

If that’s the case – and I’m vowing to you that it is – then why on earth am I sitting in a middle school gym on a lovely Tuesday afternoon watching my students having a blast at a time-based, test-driven, zero-sum math competition?

Setting the Stage for Change in the Gymnasium

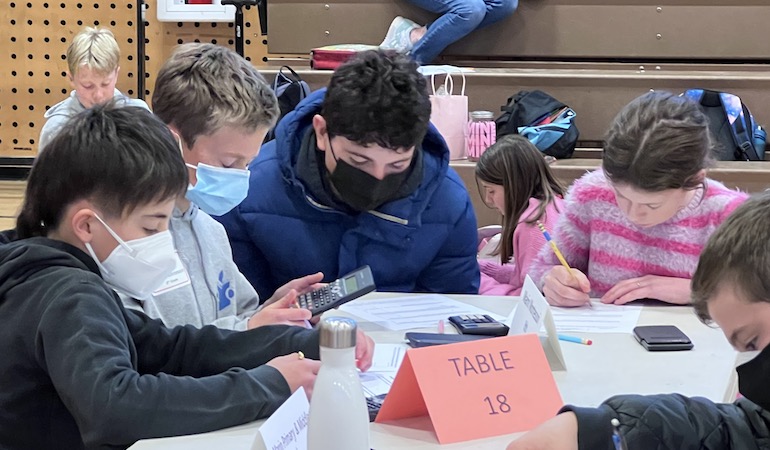

There’s a buzz of energy at the Davidson Middle School gym as the meet’s organizers welcome participants, coaches, and chaperones, help everyone complete their rosters, and find their assigned places. I struggle to make eye contact with anyone not “working” at the competition.

Everywhere in the gym, adolescents are on their phones. This phenomenon always catches me off guard, but then I remember this is normal. I am the weird one here. My years teaching in a Montessori school have given me an uncommon expectation of modern teenage behavior.

Even on their phones, students are milling about, talking with friends and parents and teachers, grabbing pencils and calculators, and eventually finding their tables. The bleachers are about half-full with a mixture of calm, excited, and anxious parents and guardians. Cans of carbonated beverages, as well as boxes of salty and sugary snacks sit unopened, waiting for the end of the meet. I suppose mathletes need their electrolytes, too.

Finally, the meet director asks for silence and reminds everyone of the rules. Students complete individual problems on half-sheets of paper in the specified time frame. Credit is awarded for precise, accurate answers.

Problems are also projected on a large screen overhead, so parents may (and many do) complete the problems along with the participants. I begrudgingly accept that I would most definitely be one of those parents doing the problems in the bleachers.

Each break between problems allows coaches and chaperones to collect answer sheets, ensure names and schools are properly recorded, and rush them to the coaches (in a separate building) doing the marking. It’s also an opportunity for students to check around the room, compare solutions with teammates, and reset before the next problem is distributed.

I observe a noticeable hierarchy in many of the teams, especially among the boys. Confidence in a solution is dependent upon consensus with the “alpha” of their team. Agreement brings bragging rights, while disagreement results in embarrassment and teasing. The competition seems to be greater within the teams, than between the teams.

What Changed My Skeptical Mind

I stick to my official coach’s duties – observing a specific table and, eventually, marking questions — and take it all in. I am unsettled because what I’m seeing is almost the precise opposite of the relationship with math that I hope to inspire in my students.

I teach at the Marin Montessori Junior High, which means I work with 13-15-year-olds, who are uniquely sensitive to negative comparisons with peers, whether it’s physical appearance, social status, athleticism, grades, or math competition scores.

They are at an age for both intense fascination and selective apathy in their excitement about mathematics, and my goal, at its most basic, is to continue nurturing their love of learning and sense of agency. Just don’t ruin their interest and confidence in math. And yet, my years of teaching tell me that this kind of math experience ruins math for more students than it will inspire.

I am not very optimistic.

But I’m still here. My students want to be here. In fact, the Marin Montessori School mathletes team is entirely student organized. They coordinate team meetings, discuss practice problems, and troubleshoot solutions from the previous meets. They even email to coordinate parent drivers and chaperones, so everyone has a ride to the meet and a ride home.

In fact, it’s the students’ attitudes and resilience that made me rethink my initial and instinctive dismissal of this kind of competition.

- “I wanted the experience of doing math with people who enjoy math and make a team of people who were interested in learning,” said Junior High student Asher Kastner. “Even if they didn’t do great, they really wanted to learn and have a good time.”

- “I wanted to get the experience of ‘mathletes’ – big crowds, challenging math problems, feeling confident under pressure,” said Shyla Woolf, another current MMS Junior High student.

But what about the competition? The winning? When asked, both students had a similar response. Did it bother them?

- Asher: “No. At first, we did, but what we cared about at the end was learning and having a good time. We measure our growth in our improvement from one meet to the next.”

- Shyla: “No. I was mostly there to learn. I made some silly mistakes the first time and felt disappointed, but never felt disappointed about not winning. It felt like a success since I learned from it.”

And what about the parents?

“There was quite a bit more parent involvement with the other schools and a significant atmosphere of pressure,” noted Jeff Gossett, parent of a Junior High student. “A lot of emphasis was placed on the awards ceremony at the end.”

But I didn’t see that with our kids.

I noticed how gracious the students were. They always pushed in their chairs, cleaned up their tables, supported one another, as well as their opponents, and were “good sports” in the best possible sense. While other tables were left strewn with snacks and empty cans and plastic bottles (while the MC pleads for teams to “support the cleaning staff”), ours looked spotless. And our kids were still all smiles.

It slowly dawned on me that our students very much still experienced math anxiety, and yet, they overcame it. As my colleague and fellow coach Gary Holsten said, that first meet was a pressure cooker. They could have easily quit and retreated to the safety of the junior high math classes. And yet they didn’t. They learned from it. They adapted. They finished middle-of-the-pack the last few meets, but continually got better, and considering the size of our team and student body compared to the other schools, it was an absolute win.

When asked what she learned from the experience, Shyla explained, “I feel much better under pressure with regard to math. And I collaborate better with teammates.”

Comfort under pressure? Better collaboration with classmates?

Maybe this mathletes thing isn’t so bad…

Seth has been teaching teens and adolescents since 2005 and brings a wealth of experience to Marin Montessori School. Besides teaching in both public and private schools, he has taught at-risk youth at an alternative learning center, international students at an IB World School, and Japanese students through the JET Program. The Montessori adolescent environment is his favorite place to work with young scholars. Born and raised in Minnesota, he graduated from St. Olaf College with a degree in mathematics education. He also completed two years of graduate-level work through the University of Minnesota. In his free time, he enjoys just about any kind of exercise but especially cycling. And he is a huge fan of all Minnesota sports teams.

Liz Kroschel

Sounds like a win not only for students and parents, but teacher as well!

So glad you do this work – you make a difference.