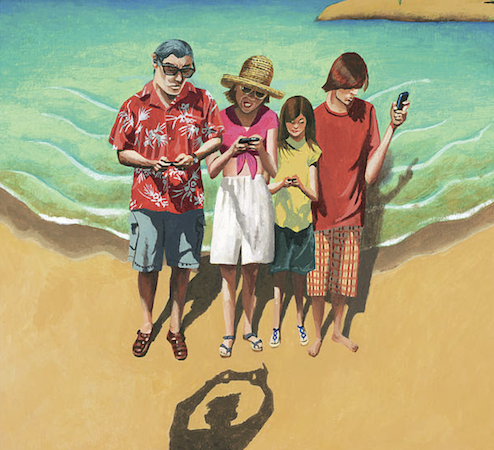

When I saw this New Yorker cover several years ago I could not take my eyes off of it. As we live through our society’s digital-technological revolution, it symbolized, in playful yet somewhat dystopic imagery, the heart of a concern I was feeling—and still do to some degree. The synopsis to the outstanding PBS Frontline documentary “Digital Nation” puts this feeling into words well: “Over a single generation, the Web and digital media have remade nearly every aspect of modern culture, transforming the way we work, learn, and connect in ways that we’re only beginning to understand.”

We are in the midst of a digital technological global revolution, one that is analogous in the profundity of its change-impact to the industrial revolution itself. Internet connectivity and digital devices are re-wiring society, and perhaps even our brains, as we know them. As Dr. Edward Hallowell writes about our lives today, “While we have grown electronically super-connected, we have simultaneously grown emotionally disconnected from each other,” and the reality of today’s modern work environment is that “…due to its speed and a volume of data unprecedented in human history, [the work environment] can gradually overwhelm and suffocate the human brain, extinguishing not only human moments but also neurons in an individual’s cerebral cortex.”

As the Head of School for MMS, charting our direction toward the future, I often ask myself this question: as an institution committed to educating children and adolescents for the world they will enter as adults, how should we respond to this revolution?

While I immediately connect with—both as an educator and a parent of teenage sons—and tend to agree with the premise of canary-in-coal-mine warning articles like The Atlantic’s, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?” or the incredible documentary one of our own MMS parents recently co-produced, Screenagers: Growing up in the Digital Age, I also know that historically, moral and societal panic have always come part and parcel with profound technological changes. In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates actually decried writing as something that would make humans too forgetful. Further, as Dr. Laura Flores Shaw summarizes below, there were once even serious people who invoked panic over the “book situation”:

In 1545, Swiss scientist Conrad Gessner, concerned about information overload, wanted “kings and princes” to do something about the “confusing and harmful abundance of books.” By 1685, the “book situation” was seen as even more dire. Adrien Baillet, René Descartes’ biographer, warned that “the multitude of books which grows every day in a prodigious fashion will make the following centuries fall into a state as barbarous as that of the centuries that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.”

Who can forget, too, the moral panic about rock ‘n’ roll that swept through our country last century (those crazy-making Beatles!)? How do we then, sort through the current histrionics and hyperbole about either the utopian promises or damaging impact of digital devices and connectivity, and get to the heart of what is true and what matters for us: raising and educating our children well.

A piece in Business Insiders called, “An MIT Psychologist Explains Why So Many Tech Moguls Send Their Kids to Anti-Tech Schools,” includes this fun line: “To safeguard their kids, tech worker parents often send their kids to Montessori schools—elite schools that focus less on tech and more on building a child’s emotional, social, and intellectual well-being all at once.”

However, the article misstates something: Montessori education is not anti-tech education. Rather, we are anti-passive learning and pro-student agency and engagement, and we are very pro-focus. Montessori education is about “preparation for life”: it is not a protective bubble fantasy.

We are preparing our children for lives as high-functioning, independent adults who create and contribute, and we can be sure that they will enter a digital technology-saturated world. While much of the research is actually still inconclusive about the true impact of digital technology on children’s development, academic learning, and emotional health, a few conclusions are apparent enough to support key emphases for our school. To prepare positively our children for this future we must do the following:

- Maintain our crystal clear commitment to learning environments and experiences that grow focus–a quality that research has already demonstrated is cultivated most powerfully in authentic Montessori education. The writings of Nicholas Carr are worth paying attention to. From his piece in The Wall Street Journal, “How Smartphones Hijack Our Minds: Research Suggests That as the Brain Grows Dependent on Phone Technology, the Intellect Weakens” or his book, The, we learn that the ability to focus, to think deeply, complexly, and problem solve is quickly becoming a rarer and thus a more valuable capacity to possess in this new world. Daniel Goleman, the science journalist whose breakthrough research on emotional intelligence is well-known and well-publicized in Harvard Business Review, recently wrote a book arguing this point: that focus is the “hidden driver of excellence” (a great KQED forum interview with him here).

- Community connectivity is key. We all, and especially children and adolescents, learn best when we engage together in appropriately complex, contextualized, and meaningful lessons and experiences. The research on the actual benefits of “educational apps” and laptops in schools is generally quite disappointing. The passivity and distraction that these tend to engender often lead to harmful or at least neutral effects. We will continue to emphasize the power of real human community. We will develop in children and adolescents the capacity to listen well to each other, to empathize, and to collaborate. Additionally, we will continue to guide them in becoming skillful in developing and maintaining healthy social relationships. This is vital: As a mountain of studies has shown recently, social connectivity is one of the most powerful predictors of happiness and even longevity of life.

- Keep it real (world). As Maria Montessori argued, children learn best through their hands. For our youngest children, kinesthetic, beautiful, and complex materials that they manipulate with their hands continues to be the most powerful tool for early childhood education (see this piece in The Atlantic, “The New Preschool Is Crushing Kids: Today’s young children are working more, but they’re learning less.”) Not long ago, I spoke with an MMS alumna who shared the story of the math teacher in her selective Marin County independent high school keeping her after class and demanding that she show him how she reached the correct answer on a complex math homework problem. After she showed him her process he praised her as using the most creative approach to math he’d ever seen. She attributed her ability to her earliest experiences in our Montessori classroom in which the math materials formed robust cognitive capacities for deep mathematical thinking—not just rote memorization. Keeping learning connected to the real world must continue throughout our programs, from the “going out” approach in Elementary to the microeconomic business ventures in the Junior High. When learning is connected to the realities and the physical spaces our children occupy, their curiosity stays fired up, and their thinking goes deep.

About a decade ago I spoke with Brewster Kahle, one of the country’s internet pioneers. I asked him, “What do you want those of us in education to do to prepare students for this new digital world?”

I’ve never forgotten his response: “Well, I can tell you what we don’t need: we don’t need passive consumers of technology. It’s easy to learn, and by the time you learn it, it’s outdated. What we need are creators. Students who can innovate and think creatively with technology.” This is why I believe that in Primary and Elementary levels, children need to develop the cognitive structures and capacity for both focused logical and creative thinking. Computer coding itself is really about language and logic, and so learning to code can be highly supportive of beneficial cognitive development, and for younger children, like in Finland, they can “…Learn Computer Science Without Computers.”

Let us teach our children to harness the wonders of the digital age to enhance their connections with others: to learn and relate and experience vibrantly, using digital technology as a tool to enliven the human experience, not replace it. For we know that when we reach the end of our days and look back on our lives, it will be the moments when we paid attention and we loved that matter most. The moments we connected with others or with nature or with a pet or with ourselves. The moments when we were present enough to open our hearts to others and to our lives with love.

This is where the richest meaning of our lives and children’s lives will be found. While many revolutions of change have and will continue to sweep through human civilizations, some simple human truths continue on. Be present. Be loving. Quietly. Simply. Beautifully.

As Head of School, Sam is responsible for ensuring that Marin Montessori flourishes and that the School’s mission is brought to life each and every day.