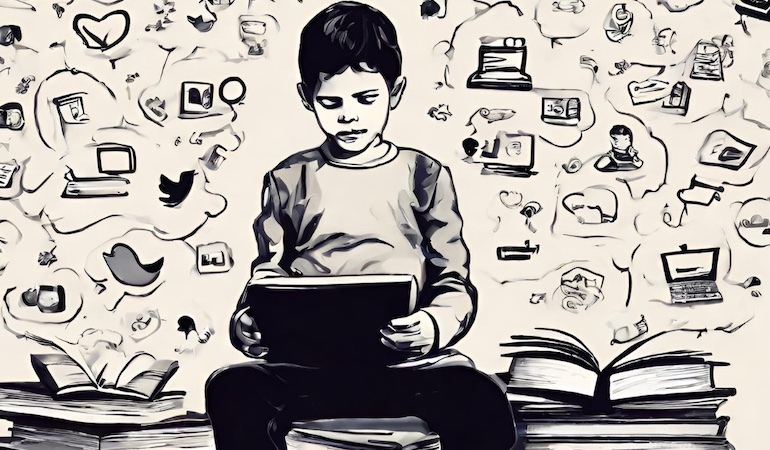

In an era of digital sound bites, where Twitter’s 280 characters often define the boundaries of expression, there’s a pressing concern about the evolving nature of communication. The onslaught of condensed digital communication modes has inspired an environment where the depth of language and profound conversations seem to be ebbing.

As a high school English teacher, I saw the shift in real-time. In 2005, the juniors and seniors I taught would unpack the poems and novels I presented with care – even if they moaned about the amount of reading I asked of them.

By the time I departed for Marin Montessori School in 2021, far too many students in my upper-level seminars simply couldn’t sustain the concentration and engage in the critical thinking necessary to unpack the meaning in texts – let alone craft the analyses that would capture and deepen their thinking.

In this new world, how do we mold our children into eloquent writers and voracious readers?

The Deepening Crisis: Succumbing to Brevity

Recent studies, such as one from Microsoft Corporation, suggest that the average human attention span has dipped from 12 seconds in 2000 to eight seconds today. This is a jarring revelation, especially when we consider that a goldfish reportedly has an attention span of nine seconds.

As platforms promoting abbreviated content rise in popularity, there’s a profound disconnect between the digital modes of interaction and the comprehensive linguistic skills that form the bedrock of human communication.

Moreover, the quest for “virality” can encourage all manner of base behavior. There’s a bottomless well of content that enflames and entertains – and not much of it carries the depth and power of the written word.

We’ve known for a long time now that we process images – especially moving images – very differently than how we process the written word. In 1985, Neil Postman published Amusing Ourselves to Death, which argued, among other prescient points, that:

“Television is our culture’s principal mode of knowing about itself. Therefore — and this is the critical point — how television stages the world becomes the model for how the world is properly to be staged.”

His point: our visual popular culture establishes the expectations all of us have as we evaluate what is worth considering in the world we encounter. And those expectations largely revolve around whether we’re immediately gratified and amused.

Now consider that Postman made this argument before the advent of the internet, let alone TikTok. In this ecosystem, the depth of literature has a hard time competing with the pleasures of the shallows.

Montessori’s Beacon in the Digital Fog

Gratefully, all is not lost.

Dr. Montessori’s approach, which transcends time and remains as relevant today as ever, offers an enriching path. By understanding the intrinsic nature of childhood development and promoting comprehensive linguistic growth, Montessori education stands as a beacon in this digital fog.

1. Tapping into the Absorbent Mind

Children in their tender years possess what Dr. Montessori aptly termed the ‘absorbent mind’—a phase where they effortlessly soak up knowledge. “The only language men ever speak perfectly,” Dr. Montessori wrote in The Secret of Childhood, “is the one they learn in babyhood, when no one can teach them anything!” This underscores the vitality of early linguistic immersion.

- Spoken Language Lessons: Transitioning from rudimentary conversations to advanced vocabulary games, these lessons underscore phonemic awareness, creating a robust foundation for language appreciation.

- Written Language Curricula: Recognizing symbols and then creating words, even before the physical act of writing, is encouraged, promoting a child’s inherent linguistic capabilities.

- Introductory Reading: Activities here not only promote reading but nurture an appreciation for it, instilling the basics of phonetic recognition, comprehension, and vocabulary.

2. Catering to the Inquisitive Minds

In The Absorbent Mind, Dr. Montessori noted, “The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled.” The Elementary Montessori curriculum resonates with this idea, lighting up young, inquisitive minds.

I spoke with our Director of Education for the Elementary, Minnie Wales, and learned quite a bit about some key Montessori principles

- Analytical Approach: Elementary children learn about the functions of words (nouns name things, articles go with nouns, adjectives describe nouns, etc.) and the functions of their parts (root words and affixes) in order to develop a deep understanding of words, how they are built, and how they are used. They then analyze sentences and their parts as well as paragraphs, longer compositions, and the role of punctuation. This work leads to a profound understanding of language mechanics.

- Literature and Articulation: Exemplary writings inspire children, teaching them the richness and diversity of expression. The children are introduced to literature during read-aloud and silent reading times. During the Upper Elementary years, they also study literature and style, analyzing and dissecting different literary works to better understand the tools and techniques used by authors.

- Key Components of Reading: This includes honing phonemic awareness, phonics, reading accuracy, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Reading practice takes place during silent reading time as well as during work time. The children are inspired to read in order to pursue their interests until their curiosity is exhausted.

- Holistic Writing Development: Children are taught not just to write, but to express, articulate, and convey, turning them into effective communicators. The Elementary writing curriculum starts with a story about the first humans who wrote things down. The children leave this lesson inspired to join the long history of writers who came before them and who are able to communicate with one another even when they are not together. From here, the children learn to build words, sentences, paragraphs, and essays (and poems and scripts and arguments and narratives…) to share their learning and convey their thoughts with more and more precise and interesting language.

Here at MMS, once children are writing words and sentences in the Elementary classes, their first bigger writing projects are often ‘studies.’ These are research projects through which the children read about topics of interest, process and write the information in their own words, and often illustrate what they have learned.

In the Lower El classes, studies can be quite long, providing opportunities for lots of reading, thinking, and writing practice. In the Upper Elementary, the children write shorter pieces with the goal of perfecting their writing skills and the quality of their creative accompaniments.

Children are motivated to work on these studies because they can study anything they are curious about. The work is driven by their own interests. And, the classroom Guides can use the study work as a medium for practicing whichever writing skills the children need.

Early in the Elementary, children practice capitalizing the first letters of sentences and proper nouns. They might then move on to end punctuation. When the children are older, they will learn about commas between independent clauses in compound sentences, and this will become a focus in their writing.

Eventually, when they work on style, they will learn the importance of using adjectives to make their writing more descriptive, and this will become a focus. The study is the means by which Elementary children practice all of the writing mechanics skills they learn while continuing to learn about topics of interest.

Rediscovering Depth Amidst Digital Superficiality

The Montessori way, rooted in holistic development, ensures children not only navigate but thrive in our ‘Twitterized’ reality. While short-form content has its merits, the foundational principles of Montessori education ensure our future generations remain adept, articulate readers and writers.

As Dr. Montessori beautifully encapsulated in The Absorbent Mind: “Our care of the child should be governed, not by the desire to make him learn things, but by the endeavor always to keep burning within him that light which is called intelligence.”

Even in the digital age, the Montessori approach ensures that this flame of intelligence— especially in the realm of language—burns bright and steady.

Terry is the Director of Communications and Story at Marin Montessori School. A classroom teacher for 30 years, he manages Grounded and Soaring.